© 2025 Glen Munro. All rights reserved.

The Forgotten Journey of Elizabeth Mary Thompson is a work of historical fiction based on documented experiences of British Home Children. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations used in critical articles or reviews.

Elizabeth Mary Thompson: A Child of Two Worlds

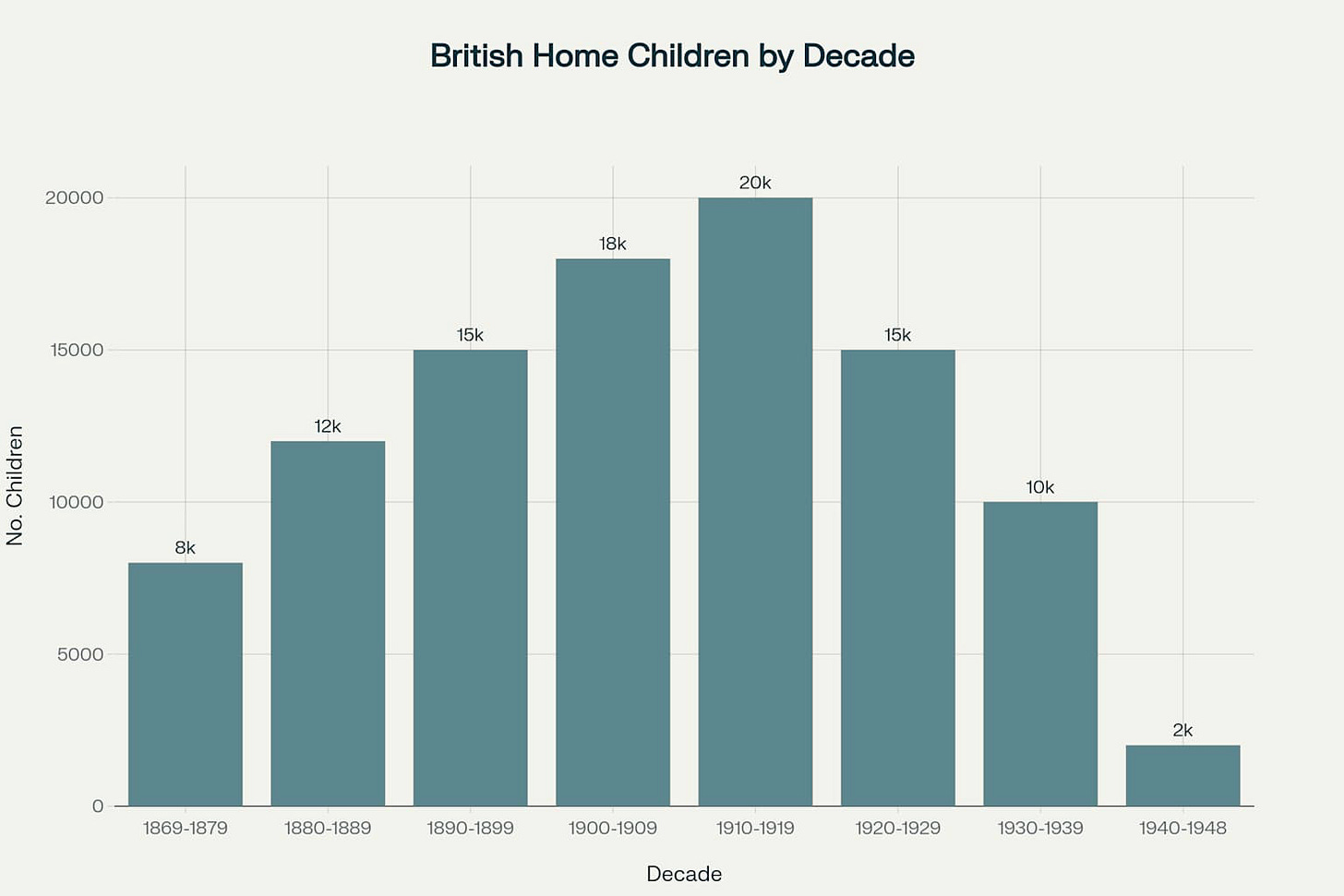

Elizabeth Mary Thompson's life began and ended in obscurity, but her journey embodied one of the most significant yet overlooked chapters in British and Canadian history. Born into the industrial grit of Hartlepool and swept across the Atlantic as part of the British Home Children migration scheme, her story represents the experiences of over 100,000 children who were sent from Britain to Canada between 1869 and 1948. Although Elizabeth herself is fictional, every detail of her journey reflects the documented experiences of real children who endured this extraordinary upheaval; their voices were largely silenced by shame and stigma until recent decades.

Chapter 1: The Industrial Heartland

Elizabeth Mary Thompson drew her first breath on a cold November morning in 1898 in Hartlepool, County Durham, as the North Sea winds carried the acrid smell of coal smoke through the narrow streets. The town that welcomed her birth was a testament to Victorian industrial ambition, transformed from a medieval fishing village into one of Britain's major coal export ports. By 1900, the two Hartlepool ports had become one of the four busiest ports in the country, with West Hartlepool alone boasting a population of 63,000.

The railway's arrival in 1835 had made Hartlepool a crucial link between the Durham coalfields and the wider world, and by the time Elizabeth was born, the town pulsed with the relentless rhythm of industrial progress. Coal wagons thundered along the tracks day and night, their cargo destined for London's factories and the furnaces of distant lands. The docks never slept—a symphony of steam whistles, clanging chains, and shouting stevedores that echoed across the terraced streets where families like the Thompsons eked out their existence.

The Thompson family occupied two cramped rooms on the second floor of a terraced house in Victoria Street, just three streets back from the West Hartlepool docks. Their home, like hundreds of others in the area, was a monument to functional poverty—red brick walls blackened by coal dust, windows that rattled with each passing wagon, and a shared privy in the back court that served six families.

Thomas Thompson, Elizabeth's father, was a stevedore who had worked the dangerous docks for fifteen years since arriving from Sunderland as a young man seeking better wages. At thirty-two, his hands were already gnarled from handling rope and chain, his back permanently bent from years of loading coal wagons. He earned eighteen shillings a week when work was steady, but dock labour was notoriously irregular, dependent on weather, ship arrivals, and the whims of foremen who chose their crews each morning from the crowd of hopeful men gathered at the dock gates.

"Come on then, lads," Thomas would mutter each morning at five o'clock, pulling on his heavy boots in the darkness. "The ships won't load themselves."

Elizabeth's mother, Mary Thompson, née Hartwell, was twenty-eight and had been taking in washing since before Elizabeth was born. Her day began before dawn, heating water in the copper boiler that dominated their tiny kitchen, scrubbing clothes with harsh lye soap that left her hands permanently reddened and cracked. She charged sixpence for a full washing, but few of her customers could afford to pay regularly.

"Elizabeth, pet, come away from that window," Mary would call to her daughter, who often pressed her face against the grimy glass to watch the constant parade of coal wagons below. "That dust will get in your chest something fierce."

Despite their poverty, the Thompson household maintained the fierce pride common among Hartlepool's working class, where a man's worth was measured by his willingness to face the daily dangers of dock work. Thomas had survived two serious accidents in his career—once when a coal wagon had pinned his leg, leaving him with a permanent limp, and another time when a crane cable had snapped, missing his head by inches.

Elizabeth's earliest memories were of her father returning home each evening, his face and clothes black with coal dust, carrying her on his shoulders despite his exhaustion. "Tell us about the big ships, Da," she would plead, and Thomas would describe the vessels that arrived from Newcastle, Scotland, and even Norway, their holds empty and waiting to be filled with Durham coal.

"There was a beauty today, our Lizzie," he would say, settling into the single wooden chair by their small fireplace. "Three masts she had, and a figurehead carved like a mermaid. The captain said she was bound for Hamburg with our coal."

Mary would listen while mending clothes by candlelight, occasionally interjecting with gentle corrections. "Don't fill the child's head with too many stories, Thomas. She'll be wanting to sail away herself."

The family's Sunday routine was sacred—attendance at St. Luke's Church, where Elizabeth learned her letters in Sunday school, followed by their one proper meal of the week if Thomas had been paid. Mary would prepare a small joint of mutton with potatoes, and they would eat together at their single table, Elizabeth perched on a wooden crate that served as her chair.

But poverty was a constant companion. During the winter of 1902, when dock work was scarce and Mary's washing customers couldn't pay, the family survived on bread and dripping for weeks. Elizabeth, then only four, developed a persistent cough that Mary attributed to the damp and coal dust that permeated their home.

"She needs proper food," Mary confided to her neighbour, Mrs. Weatherby, as they hung washing together in the shared courtyard. "But proper food needs proper money, and that's what we haven't got."

Elizabeth's world shattered on a fog-shrouded morning in March 1904, when Thomas Thompson met his fate at the hands of industrial negligence that was grimly routine in Hartlepool. The tragedy unfolded at Coal Dock Number Three, where Thomas was part of a crew loading the merchant vessel Tyne Endeavour.

The morning had started like any other. Thomas kissed Mary goodbye at half past five, promising to bring home his wages that evening. "Mind you get a nice bit of fish for our supper," he told Elizabeth, ruffling her hair. "Your da's going to have a proper payday."

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Media Glen to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.